THEMATIC ESSAY

Abstract

This essay speaks about my own exploration into how people use all of their communicative knowledge, whether consciously or not, in their search for meaning. That language may be verbal, written, or gestural. It may include dance, tonal variation in speech, literature, music, or any two or three dimensional form of art.

I will discuss the differences between translanguaging and code-switching. I will show specific examples of translanguaging using different forms of creative expression. And I will show that by using as many forms of creative expression at hand, a student will increase their entire communicative repetoire.*

* (use of repertoire in this context from Ofelia Garcia, Professor at the City University of New York, The Graduate Center, Urban Education Program)

Keywords: translanguaging, code-switching, language, multilingual, visual art, movement, gesture, education, communication.

Translanguaging through Creative Expression

Documents: unless otherwise noted, all documents listed are direct links.

Podcast_1_ Interview with multilingual about Translanguaging:inserted into essay

Sandanona_ Presentation with the same title

AP_1_Teaching Autobiography CDA_1_English Language Introduction_Adult Refugees, Same Classroom, Different Countries

Translanguaging (the subject of my Sandanona presentation) is a bi-lingual and multilingual person’s use of their internal mental grammar, their communicative resources, which encompass the entire depth and breadth of all the languages they know. An advantage of the process is a greater comprehension of language use, and being able to inherently transfer metalanguage comprehension from one language to the understanding of another. For example, when learning a new language, because of their knowledge of other languages, translanguaging enables them to be able to use this awareness of how their target language differs from, or is similar to, their L1 - or 2 . It differs from code switching, which is a deliberate, external choice between languages in the same conversation. An example of code-switching is when we use foreign words to express a thought because they are commonly used, shorter, more pointed, or sound better in the sentence, etc. Some examples among English speakers: bon voyage (have a good trip), en masse (in a large group), modus operandi (way of doing things…mode of operation), persona non grata (unacceptable - a person without status).

Other uses of code-switching lie in how we change our vocabulary and/or tone to accommodate social environs (slang, jargon, or SAE) . We may speak differently with our friends, our family, strangers, our colleagues. We may choose specific emotional tones within any group.

“I’m defining translanguaging as sense-making bilingual practices from the speaker’s perspective, and not from a language perspective as code-switching has often been studied. It’s more than just from a speaker’s perspective, it is from a bilingual speakers perspective, and not from a monolingual or monoglossic perspective. ”

“I have one language repetoire from which I select features that are appropriate to communicate.”

She speaks about multilingual acquisition through a translanguaging lens.

As a visual artist and writer, I see language as one tool of art. And, as with art, I see language as

a tool of power. This central vision of mine - the power of art and the power of language - is the impetus for my essay and defines my pursuit in this method of teaching language. In a definition

of the artist, and in alignment with my own passion, I quote this statement...

“What do you think an artist is?… also a political being, constantly aware of the heartbreaking, passionate, or delightful things that happen in the world, shaping himself completely in their image. How could it be possible to feel no interest in other people, and with a cool indifference to detach yourself from the very life which they bring to you so abundantly? No, painting is not done to decorate apartments. It is an instrument of war”

I like to think of teaching language translanguagingly (a word?), analogous to transnationalism.

An example of this analogy is the education of the Dominican Republic’s community in New York

City in 2002.

“…people like us have the best of two worlds. We have two countries, two homes. It doesn’t make any sense to be either this or that. We’re both.”

The article was written to make a case for changing ELL education in New York City from a transitional to a transnational focus. There are many socio-cultural conflicts which affect the Dominican community adversely and retard their ELL. Those conflicts actually reinforce my alignment with the benefits of using translanguaging in ELL classrooms: benefits for the language acquisition itself, but also in developing the thought processes and self esteem of students. Their L1 and English would be given equal respect. As policies stood at that time (I have not yet found evidence that NYC schools have improved their ELL teaching), their Spanish was denigrated by

the city education system and the rest of the Hispanic community. Socially, the Dominicans were dismissed because of their darker skin, their association with drug trafficking and gangs, and their accent. This widespread dismissal of the community has led to its self-denigration. And this self denigration leads to school dropouts, and refuge in the undercurrent of gang related social support.

The need for concurrent academic skills and studies in historical and cultural aspects of both the Dominican Republic and the USA, is essential. Because these students move between the two countries frequently, shuttling between educational policies which do not prepare them for full inclusion in either country, their sense of inferiority is reinforced. They need linguistic and cultural fluency in English, and they need equal fluency in Spanish, to excel in their transnational world.

My assessment coming out of this picture, which is not unique to this community, is that translanguaging, along with high levels of a full academic program in both languages, would lead

to the highest level of education and life success for the bi-lingual - multilingual - student

Andy Brown, Translanguaging: A multilingual Learning

He is a fifth grade ELL teacher in an ELL classroom at PS 153, Queens, NY. He teaches all subjects for this class using this method. The video illustrates his effectiveness using the method in language and other academic subjects. It shows how his respect for the students’ entire linguistic and cultural heritage raises their willingness to participate in class without being afraid of failure. He includes the students in building his lessons, both cuturally and socially. For example, calling on a student to try to read an assignment that was difficult for her, he says to the class, “S’s mom speaks Polish, and S is learning Polish. …(then, referring to the assignment)…wanna give it a shot, S?” And then says, “Since I don’t speak Polish, M helps me out with…what do you call that (repeats Polish word supplied by child)…translate, that’s it.” And then thanks the student (S) for a good try. It’s clear to me that his method elevates the students’ academic, social, and cultural learning. He is building a community in that class. Here is a board note showing some of Andy’s translanguaging.

In my Curriculum Design Course, I based my culminating lesson plan on the creation of community, and feelings of inclusion in a class, for the greatest language learning. Feeling safe - welcomed - relaxes the mind. The student feels free to experiment - to try out their new tongue. (CDA_1)

Another example of the effectiveness of translanguaging, used by a teacher who speaks only English, is this video about ELL groups in a K-8 school in Chinatown, NYC. The teacher has her students create their own graphic novels (another art as language form), using their entire language repertoire.

She uses culturally relevant mentor texts in graphic novels as language learning tools, and encourages their L1 usage for complex thinking. They use English for what she has already taught. She also allows students to process their ideas together, aloud, in whatever language they wish. As the students develop complex thoughts in their L1, and then distill them into their particular level of English, they excel in understanding metalanguage of vocabulary and syntax.

“The more effectively we communicate with others, the more effectively we can be our true, human, selves.”

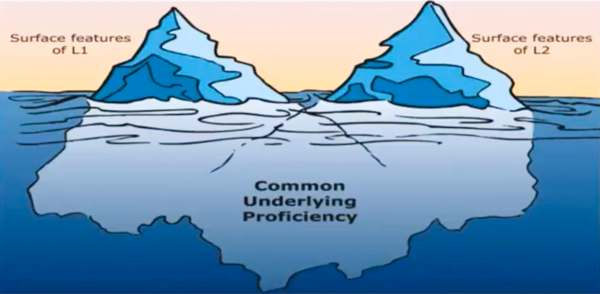

The above diagram is from, “Teaching for Cross-Language Transfer in Dual Language Education: Possibilities & Pitfalls,,” Jim Cummins, University of Toronto (Presented at the TESOL Symposium on Dual Language Education: Teaching and Learning Two Languages in the EFL Setting September 23, 2005 Boğaziçi University Istanbul, Turkey)

“In concrete terms, what this principle means is that in, for example, a Turkish-English bilingual program intended for native speakers of Turkish, English instruction that develops English reading and writing skills is not just developing English skills, it is also developing a deeper conceptual and linguistic proficiency that is strongly related to the development of literacy in the majority language (Turkish). In other words, although the surface aspects (e.g., pronunciation, fluency) of different languages are clearly separate, there is an underlying cognitive/academic proficiency that is common across languages. This common underlying proficiency makes possible the transfer of cognitive/academic or literacy-related proficiency from one language to another.”

Cummins analyzes the case for using translanguaging in the classroom for optimum language learning. His figure on the left shows how a target language is usually taught: as though the mind compartmentalized its knowledge (Separate Underlying Proficiency); as though we ignore and separate our linguistic reservoir. On the right, we see translanguaging in use (Common Underlying Proficiency).

SUP CUP

(Cummins, J. (1981, The role of primary language development in promoting educational success for language minority students. In California State Department of Education (Ed.), Schooling and language minority students: A theoretical framework (pp. 3-49). Los Angeles: California State University, Evaluation, Dissemination and Assessment Center. Cummins, 1981):

In my internship, I took advantage of students’ L1’s many times. As they began to acquire more vocabulary, I often had them use their proficiencies in their L1 to help them develop a greater understanding of English grammar. They would use their L1’s amongst themselves to explain the English to those for whom it was more difficult. I would reach out to them during a lesson to ask how they would say a word in their L1 that they were studying in English. I would then repeat the L1 myself. You may imagine how amusing that was for them. I would practice my pronunciation of their L1’s - with their coaching - and they would be encouraged to speak in English. This was all part of what I like to call my “spiritual scaffolding:” the community building I hold as the foundation for optimum learning in class. I observed that when they explained something amongst themselves in their L1, they were able to understand the concept in English much more quickly. They were emboldened to speak English when I shared lessons in this way. I used translanguaging with other forms of communication. Dance, gesture, music, and drawing were media I employed in every class.

We would demonstrate differences in body language in different cultures. One vehicle I used to assess their vocabulary growth, was their drawings. For example, after we played a game of Flyswatter (Students would write words of their choosing on the board in a random pattern. They would divide into two teams. One student would call out any word which appeared on the board, and the two students in the front of each team would race to see who could hit the word first. We would time their speed and, after everyone either had a turn, or it was evident that they had had enough, I would tally the scores. [I always had treats for everyone as prizes for competing, but the winners would get the treats first.]). I would then ask them to draw the nouns they had posted during the game. They learned very effectively through all the sharing and laughter in,

“that’s how - not how - you draw it!”

“Translanguaging in ELL classrooms can enable linguistic creativity and a profound engagement in a sociocultural reality.”

Because everyone has a story to tell, and dance is a way of telling a story, having students choreograph their story and then onlookers re-telling it verbally, adds great depth to their critical thinking in language acquisition. In a lunchtime presentation during MAT 47, one of our cohort had us enact our own stories with this method. It was completely engaging - and also difficult to perform and translate. We became very aware of our search for meaning and the language to express it. There we were, thrown into the translanguaging experience, and we all spoke English! This is the kind of total sensory experience in language teaching immersion, I found invaluable at SIT.

Dance tells a story. To do so effectively, a dancer must draw upon all communicative resources. Dance is a narrative; a conversation; an expression of raw emotion through movement: translanguaging.

Published on Sep 7, 2015, FINAL Crew Battle @HipHop Festival in Berlin, Filmed & Edited: Thanh-Kim Huynh, Organisation: Streetdance Connection & Ghetto Stylez, Location: Huxley's Neue Welt Berlin

In all our studies at SIT, we explored the importance of context in language use. In Sociolinguistics, we developed presentations to show how language is used in specific socio-cultural environs. I see the deliberateness of code-switching as the pre-determined use of language (eg. change of register, foreign word substitution, jargon, slang…), from one milieu to another.

“To me, translanguaging elicits profound linguistic and creative output.Through its action, it can enable us to produce our art - however the form - which enlarges our human-ness and our power to change ourselves and our world”

Let's look at an analogy from the business world.

“You may have noticed students who just try to remember and pound back what is remembered. Well, they fail in school and in life. You’ve got to hang experience on a latticework of models* in your head.”

Why do I include quotes from a business site? Because they show the importance of creative thought in the world at large. Because they show why to NOT compartmentalize, but to use all our capacity for investigation, for thinking creatively, for greater success. And we, as language teachers, have a responsibility to prepare our students for success. No matter the field of work, critical thought will lead their way. I like to see this as an analogy between code-switching as external activity of selectivity, and translanguaging as the internal activity of collectivity.

In my search for evidence of more culturally inclusive ELL teaching practices in New York City,

I came across this discouraging paragraph in a private language school website.

“Before you begin your studies at New York English Academy, you will be given a placement test to determine your level. This test will determine the appropriate level for you to start your ESL classes. Once you enter the classroom, English becomes your new language. With rare exceptions, students are required to speak English at all times while at New York English Academy.”

To me, this is linguistic exclusionary thinking. It places the student's L1 aside. In many cases,

I suspect, that L1 becomes less valued - less important. The student's L1 culture bows to cultural oppression. And, the student is cut off from the depth of their linguistic experience and knowledge.

I see language as a force for power, for inclusion, the tool which gives us the ability to fulfill our gift. Thus, it is also a force for disempowerment and disenfranchisement. Compartmentalizing a student's knowledge and using deductive approaches to language teaching, limits the depth of

a student's communicative potential.

“The best methods are therefore those that supply ‘comprehensible input’ in low anxiety situations, containing messages that students really want to hear. These methods do not force early production in the second language, but allow students to produce when they are ‘ready’, recognizing that improvement comes from supplying communicative and comprehensible input, and not from forcing and correcting production.”

To present different directions in language learning, I wrote the scripted questions for the following podcast, thinking about using translanguaging when teaching a language to multilinguals. They are a guideline for our conversation, and were not meant to be answered literally. Dora, a multi-lingual, speaks about her learning experiences and thoughts about TL. We discuss the depth of learning experience it can provide, and how it would have helped her.

1. Dora, since you are a linguist, let’s talk about how you view code switching and translanguaging.

2. Because you know more than one language, have you noticed your ability to know

which questions to ask and what metalanguage clues to look for when you study a new

- to you! - language?

3. When you speak a language, even in your L1, are you conscious of your ability to draw upon

your entire language repetoire? If not consciously, now that we are talking about it, do you think you do it? And how?

4. Have you found your ability as a multingual helpful in your life in ways that are not

specifically linguistic? How?

5. Is translanguaging used in Italy when teaching foreign languages?

6. If not, how are languages taught ?

7. As a multilingual, do you see the value in teaching languages with translanguaging?

I have always loved language, and especially the flexibility of English and its options for precise communication. My studies at SIT have thrilled me with their intellectual exploration. I have expanded my own creative and linguistic repetoire because of the MAT program. My internship taught me how to utilize every facet of my TESOL learning. Through my experience teaching English to refugees, I discovered my affinity for linguistics. When I came to SIT, I brought my understanding - and experience - of the power of communication through language of poetry and visual creative expression. Now, as I finish my studies here, I am filled to bursting with ideas about using all that I have learned and experienced. The experiential method in which I was enveloped here, has increased my own communicative power. Coupling the TESOL experience with my own highly developed artistic skill, is creating a surge of ideas. No dam can hold them back and I cannot thank you enough, my MAT faculty and peers, for what you give.